Why do people go to such extraordinary lengths to build mansions and create spectacular gardens in wild, wet and inaccessible places? In the west of Ireland there are several examples: Illnacullin on Garnish Island, Co. Cork, Kylemore Abbey in Connemara, Co. Galway and Glenveagh Castle in the Derryveagh Mountains, Co. Donegal. After a late summer visit to Glenveagh – now a national park – I decided to unearth the story of the estate and its owners.

Lough Veagh and the Derryveagh Mountains (photograph by kind permission of Avril Lehan)

The best way to experience the isolation of Glenveagh Castle and its gardens is to walk or cycle from the visitor centre along the 4 km track beside Lough Veagh. On either side of the lake are bare, rugged mountains. In the distance, on the south side of the lake, a dark patch on a promontory reveals itself to be shelter belts of Scots Pine and Rhodedendrons surrounding a nineteenth century Scottish-baronial style castle. If it reminds you of Balmoral, that is intentional. Around the castle and on the hillside behind are, astonishingly, 11 hectares of beautiful gardens and walks. There are pleasure grounds, a walled garden, a rose garden, a Belgian Walk, an Italian terrace, a Tuscan garden, a Himalayan garden, statues, summerhouses to shelter you from sun or rain, and places to enjoy the stunning views. The soil is acid, the micro-climate is mild and in summer the days are long, so among the trees and shrubs are rare and exotic flowering specimens that are distinctly non-native.

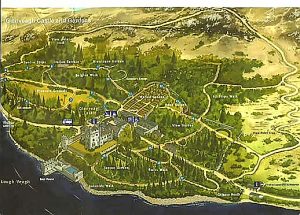

Plan of the gardens Eucryphia in flower

The Glenveagh Estate was established in 1859 by John George Adair, a wealthy Irish land speculator with business interests on both sides of the Atlantic. After the devastation of the Great Potato Famine in the mid-nineteenth century, land in Donegal was cheap and Adair bought several holdings of land to create a single vast estate (16,500 hectares). A man with big ideas, his ambition was to build a castle and hunting estate to rival Balmoral, Queen Victoria’s residence in Scotland, and perhaps to attract royal visitors. His inspiration would have come from the Highland clearances in eighteenth and nineteenth century Scotland, when tenants were evicted from land that could then be used more profitably for sheep farming or deer stalking. In so-doing, Adair also hoped to ‘improve the aesthetic beauty of Glenveagh’. Two years later, he used the pretext of the unexplained murder of his land steward to evict 244 of his tenants, making no provision for their resettlement. This disgraceful event is known as the Derryveagh Evictions and is remembered to this day. By 1873 the building of the castle was complete. But ‘Black Jack’ Adair had only a few more years to enjoy his creation: he died suddenly in 1885.

Adair’s wife, Cornelia, an American from upstate New York, took over the running of the estate after his death. She is credited with establishing the framework for the pleasure grounds by importing hundreds of tons of soil to make a lawn, starting a kitchen garden and planting the Scots Pine and Rhodedendron shelter belts. In 1915, the Belgian Walk was constructed by Belgian refugees displaced by WW1 and housed at Glenveagh. Under her stewardship, 27 kilometres of deer fencing were erected to contain the herd of red deer, kept for deer-stalking. Cornelia, a renowned society hostess, spent summers at the castle with her guests, but abandoned Glenveagh after the Easter Rising in 1916, an armed nationalist rebellion which led to Irish Independence in 1922. She died in 1921.

The pleasure grounds Oriental statue in the pleasure grounds

Glenveagh’s next owner (from 1929) was a well-known American art historian and multi-millionaire from Harvard, Professor Arthur Kingsley Porter. He had come to Donegal with his wife Lucy to study Irish archaeology and culture, and, it is thought, to escape from personal scandal and depression. But his ownership of Glenveagh was shortlived: in 1933 he disappeared from an island off the coast of Donegal in mysterious circumstances. During her time as chatelaine, Lucy introduced the single red dahlia named Dahlia ‘Matt Armour’ after her young under-gardener, which is still grown in the walled garden. In 1937 Lucy sold the estate to yet another American, Henry McIlhenny, a former student of her husband’s, who had fallen under the spell of Glenveagh whilst holidaying there as her guest.

Dahlia ‘Matt Armour’ in the walled garden

Henry McIlhenny was the grandson of an Ulster Scot from Donegal who had emigrated to America as a child. McIlhenny’s immense wealth derived from his grandfather’s invention of the gas meter, while from his parents he acquired a love of the arts and of collecting. He studied art history at Harvard and became a major collector of French nineteenth century art. Later he was appointed as a curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and eventually its chairman. (Andy Warhol described McIlhenny as the only man in Philadelphia with glamour!) He spent several summers at Glenveagh until 1941, when America joined WW2 and he enlisted in the US navy. At the end of the war and with a distinguished war record, he returned to Glenveagh, seeking peace and sanctuary. He modernised and redecorated the castle, filling it with treasures, installed a lakeside heated swimming pool and began in earnest to develop the gardens and to indulge his passion for entertaining house guests – Grace Kelly and Greta Garbo among others. McIlhenny’s hand can be seen everywhere in the gardens. Cornelia Adair’s kitchen garden acquired walls and herbaceous borders and became a jardin potager, providing cut flowers, and many varieties of fruit, vegetables and herbs for the kitchen. A Gothic orangery, designed by French illustrator and aesthete Philippe Julian, was added to the back of castle beside the walled garden.

Pathway in the walled garden The head gardener’s cottage

Aconitum and Clematis in the walled garden

Sweetpeas, Lychnis and step-over apple trees in the walled garden

Vegetables and companion planting in the walled garden

Elsewhere, the gardens acquired exotic plants, structures and statues, and new areas of the hillside were cultivated. Distinguished consultants brought in to assist with this project included Jim Russell, plant hunter, garden designer and proprietor of Sunningdale Nurseries and Lanning Roper, an American landscape architect and former fellow student of McIlhenny’s at Harvard who trained at Kew. McIlhenny loved his garden but not the climate. Even on a warm summer’s day he would venture out in hat, overcoat, scarf and gloves – and a pair of secateurs!

The Italian Terrace

In the 1970s, with the outbreak of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, McIlhenny’s friends were reluctant to come to Glenveagh. Worried by the isolation of the castle and the possibility of being kidnapped by the IRA, he entered into discussions with the Irish government about gifting the land to the State to create the Glenveagh National Park. The transaction took place in 1975, with McIlhenny retaining ownership of the castle and the gardens. He visited occasionally over the next few years but in 1983, by now in his seventies and finding Glenveagh costly to run and the weather too inclement, he gave the castle, its contents and the gardens to the Irish State and left for good. He died in 1986. It is said that he gave Glenveagh to the people of Ireland as atonement for the Derryveagh Evictions.

For anyone interested in horticulture (as I am), Glenveagh provides a superb example of what can be achieved in an extremely challenging environment. Do visit if you ever get a chance. There are many wonderful gardens open to the public in Ireland, north and south of the border. In fact a WFGA tour might a very good idea!

Glenveagh National Park is open all year round, except in extreme weather conditions. See www.glenveaghnationalpark.ie for details.

If you would like to see Henry McIlhenny ‘at home’ at Glenveagh Castle, watch the RTE documentary ‘Henry McIlhenny: Master of Glenveagh’ on YouTube.

Text and photography by Sarah Foord-Kelcey

My Basket

My Basket